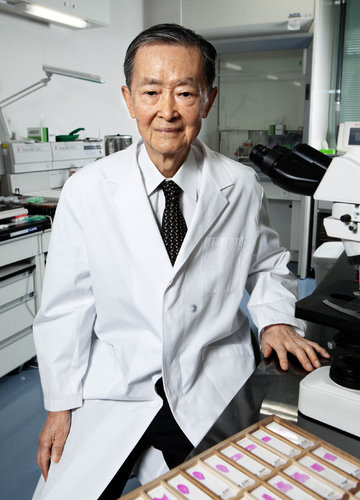

Michiaki Takahashi, 85, Who Tamed Chickenpox, Dies

The New York Times Company / Ko Sasaki

Dr Michiaki Takahashi, whose experience caring for his 3-year-old son after the boy contracted chickenpox led him to develop a vaccine for the virus that is now used all over the world, died on Monday in Osaka, Japan. He was 85.

The cause was heart failure, said his longtime secretary, Maki Fukui.

In 1964, Dr Takahashi, who had spent several years studying the measles and polio viruses in Japan, was on a research fellowship at Baylor Medical College in Houston when his son, Teruyuki, came down with a severe case of chickenpox after playing with a friend who had the virus.

“My son developed a rash on his face that quickly spread across his body,” Dr Takahashi recalled in a 2011 interview with The Financial Times. “His symptoms progressed quickly and severely. His temperature shot up and he began to have trouble breathing. He was in a terrible way, and all my wife and I could do was to watch him day and night. We didn’t sleep. He seemed so ill that I remember worrying about what would happen to him.”

“But gradually, the symptoms lessened and my son recovered,” he added. “I realised then that I should use my knowledge of viruses to develop a chickenpox vaccine.”

He returned to Japan in 1965 and within 5 years had developed an early version of the vaccine. By 1972 he was experimenting with it in clinical trials. Within a few years, Japan and some other countries had begun widespread vaccination programmes. Yet FDA did not approve the US's first chickenpox vaccine until 1995.

The delay was caused by several factors, including concerns that the immunity created by the vaccine might not last long enough, that there could be unwanted side effects and, more generally, that chickenpox might not be a serious enough disease to warrant a vaccination programme.

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella-zoster virus, a form of herpes. If a person contracts the virus, has an active infection and then recovers, the virus is not actually gone from the body. It can hide in nerve cells for years or decades, then emerge again to cause shingles, a painful condition that causes a skin rash and occurs mostly in adults.

Dr Takahashi developed his vaccine by growing live but weakened versions of the virus in animal and human cells. The vaccine did not cause the disease, but it prompted immune systems to produce antibodies.

“It fools the immune system into thinking it has seen this disease before,” said Dr Anne A. Gershon, the director of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Disease at Columbia University Medical Center and a friend of Dr Takahashi’s.

Dr Gershon said Dr Takahashi’s is “the only vaccine successful against any of the human herpes viruses.”

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began recommending a second dose of the vaccine. The C.D.C. recommends that children receive their first dose when they are 12–15 months old and a second dose when they are 4–6 years old.

“Prior to the licensing of the chickenpox vaccine in 1995,” the agency said, “almost all persons in the US had suffered from chickenpox by adulthood. Each year, the virus caused an estimated four million cases of chickenpox, 11,000 hospitalizations, and 100–150 deaths.”

Today, chickenpox — like other childhood diseases for which vaccines had been developed earlier, including measles, mumps, rubella and polio — is largely a thing of the past. A large long-term study published this year found that a very small percentage of children who receive one dose of the vaccine still get the virus, and that most of those cases are mild or moderate. Among children in the study who received a second dose, none contracted the disease.

Dr Takahashi was born on 17 February 1928, in Osaka. He received his medical degree from Osaka University in 1954. Before his work on the chickenpox vaccine, he collaborated on mumps and rubella vaccines. He later served on the board of directors of the Research Foundation for Microbial Diseases of Osaka University.

His survivors include his wife, Hiroko, and his son.

Related News

-

News Ophthalmologic drug product Eylea faces biosimilar threats after FDA approvals

Regeneron Pharmaceutical’s blockbuster ophthalmology drug Eylea is facing biosimilar competition as the US FDA approves Biocon’s Yesafili and Samsung Bioepis/Biogen’s Opuviz. -

News ONO Pharmaceutical expands oncology portfolio with acquisition of Deciphera

ONO Pharmaceutical, out of Japan, is in the process of acquiring cancer-therapy maker Deciphera Pharmaceuticals for US$2.4 billion. -

News First offers for pharma from Medicare drug price negotiations

Ten high-cost drugs from various pharma manufacturers are in pricing negotiations in a first-ever for the US Medicare program. President Biden’s administration stated they have responded to the first round of offers. -

News Eli Lilly’s Zepbound makes leaps and bounds in weight-loss drug market

In the last week, Eli Lilly has announced their partnership with Amazon.com’s pharmacy unit to deliver prescriptions of Zepbound. Zepbound has also surpassed Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy for the number of prescriptions for the week of March 8.&nbs... -

News Chasing new frontiers at LEAP – The National Biotechnology Strategy Keynote

On the third day of LEAP (4–7 March 2024, Riyadh Exhibition and Convention Centre, Malham, Saudi Arabia) the CPHI Middle East team hosted the Future Pharma Forum, to set the scene for an exciting new event for the pharma community, coming to Riya... -

News Pfizer maps out plans for developing new oncology therapeutics by 2030

Pfizer dilvulges plans to investors around growing their cancer portfolio, and the drugs they will be focusing on developing after their aquisition of Seagen in 2023. -

News Generics threat to Merck’s Bridion as Hikma seeks pre-patent expiry approval

Merck has disclosed they received notice from Hikma Pharmaceuticals for seeking a pre-patent expiry US FDA approval for Hikma’s generic version of Merck’s Bridion. -

News Bernie Sanders vs Big Pharma - the latest on drug price negotiations

In a hearing in front of the US Senate, three of the biggest pharmaceutical companies in America are challenged over exorbitant prescription drug prices, with Sanders claiming their actions are limiting the population's access to affordable healthc...

Position your company at the heart of the global Pharma industry with a CPHI Online membership

-

Your products and solutions visible to thousands of visitors within the largest Pharma marketplace

-

Generate high-quality, engaged leads for your business, all year round

-

Promote your business as the industry’s thought-leader by hosting your reports, brochures and videos within your profile

-

Your company’s profile boosted at all participating CPHI events

-

An easy-to-use platform with a detailed dashboard showing your leads and performance

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)